Teaching Your Pet Quantum Superposition

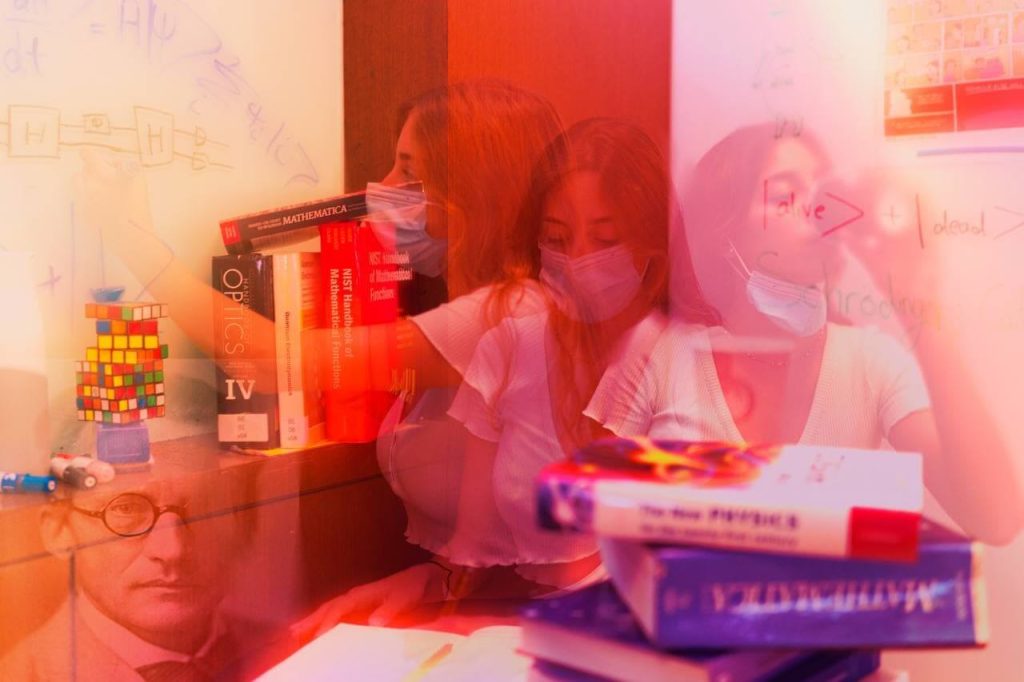

In quantum physics, the state of a physical system is often represented by a vector in a high-dimensional vector space, also known as Hilbert space. Much like adding waves in classical physics, a superposition of quantum states involves summing different vectors in Hilbert space. Applying this to NUS student Aliki, her individual tasks such as reading a book, having a drink or deriving a formula on the white board, represent a quantum superposition of her different states.

Let us now consider a physical system with two states denoted as 0 and 1, its quantum superposition is a linear vector sum with two linear coefficients. Here lies one perplexity of quantum physics—mind-boggling but not totally beyond comprehension: Observing the system to find out its state, we get 0 or 1 as two possible answers; however, as Nature has its own way, the laws of quantum physics forbids us to know which answer we get. And although this quantum state is everything we know about the system, we cannot make a definite prediction regarding the outcome of our observation.

Nonetheless, a solution has been found thanks to quantum physicists! If we prepare many identical copies of our superposed states and perform a statistical analysis over the results, a definite statistical behaviour emerges: the probability of obtaining 0 or 1 is proportional to the square of the absolute value of their respective state coefficients. This is the cornerstone of quantum theory. Counterintuitive as it may sound, even though there is nothing more we could do to increase our knowledge about a quantum system, we need to dismiss any single-event prediction and rely only on a probability approach.

Returning to the superposition of Aliki’s multiple tasks as a quantum state, it is in principle allowed, though at the macroscopic level. If we now make an observation on Aliki to find out which task she is performing, we know we will end up finding her in one of her many tasks only: Our action of checking on Aliki destroys her multitasking state! Even more baffling, we cannot predict at all which task she is found to be working on. Prof. Schrödinger certainly knew this well so he is not watching Aliki.

As we cannot prepare many identical copies of Aliki, a statistical approach is not going to be helpful right? Now imagine we wait for Aliki to complete all her tasks without looking or interfering. After all her tasks, Aliki decided to relax and watch a movie. If we follow with an observation, we then have a definite answer: Aliki is watching a movie, having completed all her tasks. This is analogous to quantum computing, which exploits the idea of quantum superposition performing multiple tasks in parallel and activating a measurement of the quantum system to reach a useful prediction only at the end of the parallel execution.