An Interview with Prof Lo Hoi Kwong

Prof Lo Hoi Kwong, Provost’s Chair Professor, Department of Physics, shares his research interests and works in the field of quantum information science.

What drew you into the world of quantum information science?

I like quantum information science because it provides sci-fi technologies based on the fundamental laws of physics. Personally, I find such a “duality” most satisfying.

I got side-tracked into quantum information science. In 1994, after completing my PhD at Caltech in Theoretical Particle Physics under Prof John Preskill (who, independently, also switched to quantum information science and became a leading expert there), I moved to the Institute of Advanced Study (IAS), Princeton, to do a postdoc under Profs Frank Wilczek and Stephen Adler. It was 1994, the year when the ground-breaking Shor’s quantum algorithm (for efficient factoring of large integers) came out. I was at the School of Natural Sciences at IAS. My neighbouring school, School of Mathematics, organised a one-day workshop on quantum computing and invited big names such as Peter Shor and Benjamin Schumacher to give seminars. We were so blown away by the seminars that a few of us (another postdoc, Dr H F Chau, Prof Frank Wilczek, and I) decided to spend time to study quantum computing together. So I was side-tracked ever since 1994.

Well at that time, it was almost a career suicide to move to a new research area like quantum computing because it was so new and there were hardly any postdoc opening. However, I somehow survived.

Looking back, it was extremely good timing for me to start to work on an exciting new research area when there were few researchers and the field was not crowded at all.

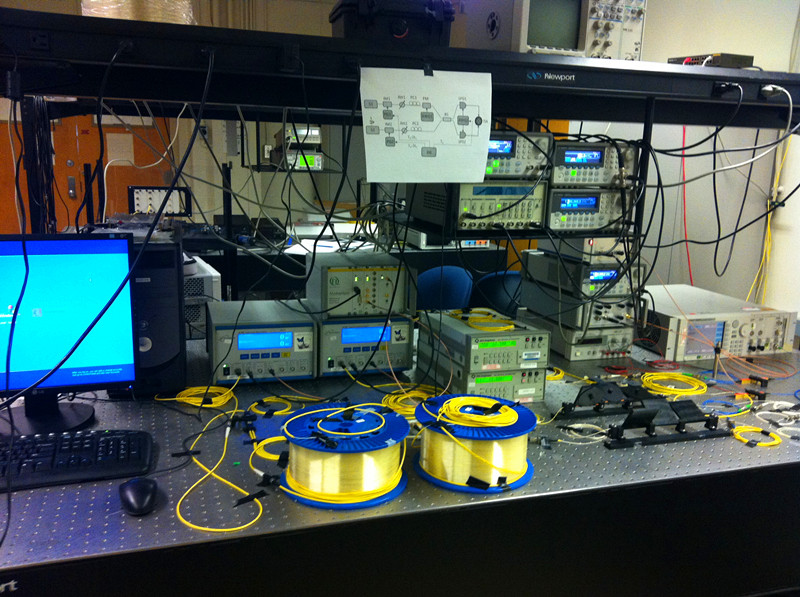

A quantum communication experiment at Prof Lo's lab at the University of Toronto.

Briefly share with us your current research interests.

I work on quantum cryptography, particularly the theory and experiment of quantum key distribution (QKD). QKD offers information-theoretic security based on the laws of physics. Specifically, the famous quantum no-cloning theorem states that it is fundamentally impossible for anyone (including an eavesdropper) to copy an unknown quantum state. So, by encoding information in polarisation of a single photon in a random manner, QKD allows two users to share a common string of numbers securely in the presence of an eavesdropper. This is classically impossible to achieve.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the space-ground integrated quantum network in China1, consisting of four quantum metropolitan area networks in the cities of Beijing, Jinan, Shanghai, and Heifei, a backbone network extending over 2000 km, and ground-satellite links. There are three types of nodes in the network: user nodes, all-pass optical switches, and trusted relays. The backbone network is connected by trusted intermediate relays. The satellite is connected to a ground-satellite station near Beijing, which can provide ultra-long-distance communications2 (Xu, Feihu, et al., 2020, "Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices," Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 025002).

Figure 1 shows an existing QKD network in China. Just like other QKD networks, it makes use of the decoy state protocol, which I provided the first security proof to. The research I have done helped to lay the foundations of the protocols that are employed in existing networks.

While QKD is secure in principle, in practice, many side channels could exist and compromise security. One area of my interest is to study the origin of those side channels and find methods to mitigate them. Besides, I am very interested in building an entirely new generation of quantum networks with untrusted relays. This will dramatically improve security by removing the need for trusted relays that exist in the current quantum networks.

Another research area of mine is in quantum repeaters. Ten years ago, my collaborators and I proposed a novel approach for all photonics quantum repeaters. I am very interested in the theory and experiment involved in pushing this concept into realisation.

What inspired you to join NUS Physics, and what do you look forward here?

Singapore is investing heavily in quantum technologies. It has announced the National Quantum Strategy, an investment of S$300 million to fuel quantum technology research here. There are many well-known quantum researchers at NUS and the Centre for Quantum Technologies (CQT) in Singapore. So, this is a very vibrant place to do quantum research.

I am very excited to indulge in quantum research in both theory and experiment in Singapore. Graduate students and postdocs are the future. It is a huge privilege for me to work with energetic brilliant young people here. Besides, I look forward to collaborating with the existing and new faculty members at NUS and CQT to build something bigger and to work with international researchers to build the global quantum community.

I have diverse experience in interdisciplinary research, working in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science and electrical engineering. Besides my decades of academic research experience at universities, I also have many years of industrial research experience at both major IT firms (such as Hewlett-Packard Labs in Bristol, UK) and start-ups (including Quantum Bridge, Toronto and MagiQ Technologies, Inc, New York). I co-founded Quantum Bridge which helped me gain insights into quantum start-ups.

Over the longer term, I hope my experience would be useful in building the quantum eco-system in Singapore.

The word “quantum” seems to conjure up mystery to many people. How would you explain quantum information science to someone with no physics background?

Welcome to the strange quantum World!

The goal of quantum information science is to unleash the full power of quantum mechanics to achieve tasks that are either impossible or very difficult in the classical world. Quantum information science is a new voyage into the strange quantum world of Hilbert space. It requires courage and suspension of (classical) beliefs. In the quantum world, we only assign meanings to what we actually observe and leave anything else (that we don’t observe) floating around in the Hilbert space waiting for our future discovery. We cannot assign any “physical reality” to the unobservable world until they are actually observed.

In the quantum world, God plays dice with the universe. The Schodinger’s cat can be alive and dead at the same time (before we perform a measurement on it).

What kinds of problems can quantum technologies solve that current technologies cannot?

Quantum technologies can be used for quantum computing, quantum communication and quantum sensing.

The killer application of quantum technology is Shor’s quantum algorithm (1994), which allows the efficient factoring of large integers. This was a remarkable discovery. Factoring is known to be hard problem with conventional (classical) computers. Mathematicians have worked on factoring for a millennium and no mathematician has found any efficient classical factoring algorithm so far. Factoring is more than an intellectual curiosity. The presumed hardness of factoring is the very foundation of the security of the best-known RSA algorithm, which is a key ingredient of our digital security. If a quantum computer is ever built, much of the conventional cryptography will fall apart!

Earlier this year, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology announced new post-quantum cryptography standards specifically to counter the risk of quantum computing.

QKD allows information-theoretic security in key distribution in the presence of an eavesdropper. Quantum simulations may allow us to simulate quantum molecules much more efficiently, thus building better batteries, chemicals and medical products.

Quantum technology is likely to change the definition of a second and may lead to more accurate Global Positioning System.

What advice would you give young students who are curious about quantum physics but feel intimidated by the subject?

The important things are to dream big, persevere and be realistic. Imagination is more important than knowledge. As for perseverance, I had one paper that took me nine years or so from conception to publication. The dream will not die until we give up. As for being realistic, for nine years, Albert Einstein could not find an academic position. Furthermore, we are not Albert!

If you have a chance to start all over again to pursue a field of study, what would it be and why?

I am quite excited by the dramatic recent advances in the experimental implementations of quantum error correction and fault-tolerant quantum computing. After decades of research, in the last year or so, researchers have finally beaten the threshold value and shown an improvement in the life-time of qubits in quantum memories using quantum error correcting codes. Recent works on manipulating neutral atoms in optical lattices are also very impressive. The connection between AI and quantum requires further exploration. With so much exciting research to be done, I think I would still pursue research in quantum information science.

1Chen, Yu-Ao et al., “An integrated space-to-ground quantum communication network over 4,600 kilometres”, Nature (London) 589, 214–219 (2021).

2Liao, S-K et al., “Satellite-relayed intercontinental quantum network”, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 030501 (2018).